Shackleton's Wake: 100 years later – Dispatch from Antarctica

Stepping ashore holding a book of Frank Hurley's photographs from 1915-16, I see the same rock formations before me as in the photo. We're standing at Cape Valentine. Today is January 6, 2015. It was here on April 15, 1916 – Elephant Island just over 100 years ago – that Sir Earnest Shackleton and his men first came ashore after 170 days camped on the ice.

Frank Hurley was Shackleton's expedition photographer and filmmaker. By the time they were marooned on Elephant island, he was frost bitten, starving, and in pain, with only a few frames of roll film left to document what would become one of the most famous moments in the history of Polar Exploration. Hurley had state-of-the-art equipment for his time, and continued to shoot strong compositions despite their perilous situation.

In contrast, my images are from a series of voyages on board the National Geographic Orion, where I'm warm, well-fed, and comfortable. Modern digital technology is lightyears ahead from Hurley's day. I can shoot an infinite number of digital images and switch to video with the push of a button. Imagine Hurley hoarding his film, like his next piece of food, wondering if his images will survive the ordeal.

If I were to meet Frank Hurley today, he would think I was from outer space, rather than the future. The way we travel today would seem so far fetched from 100 years ago.

I download and store images every day on the latest computer equipment, and store gigabytes of information. Like magic, I can see my images seconds after I make them. Today we use PhotoShop in the digital LightRoom, in place of the traditional chemical darkroom. And most amazing of all, I connect to the internet to send images over satellite from remote corners of the world.

I am thankful for the ships and professional seaman that take you there safely in comfort and style.

Reflection and Blue Light, National Geographic Orion, Lemaire Channel, Antarctica

(Canon EOS-5DIII; 16-35mm; 1/000 sec; f/8; ISO 600; - 0.67 EV)

The National Geographic Orion departs Ushuaia on December 27, 2015, almost 100 years to the day that Shackleton's famous Endurance Expedition headed south from South Georgia and into the Weddell Sea in 1915.

A window of calm weather presented the opportunity to land at both Cape Valentine and Cape Wild. It's a rare event indeed, to land on Elephant Island, one of the stormiest places on the planet. Before leaving the landing we recreate the event, but instead of the James Caird it's a Zodiac. And instead of feasting on seal blubber, we're going back to hot soup on the warm confines of the National Geographic Orion.

Shackleton's story is a well-known epic tale of leadership and survival, their ship Endurance sank after being crushed by the ice in 1915. After spending months on the ice, the expedition members clung to the rocky shores of Elephant Island. In the end, all the men survived, saved by "The Boss" following his heroic open-boat crossing in the James Caird from Elephant Island to South Georgia. Numerous books reveal Hurley's extensive archive of prints. He was clearly ahead of his time, shooting film in various formats, while also taking the time and effort to also shoot motion picture film

Our modern story written on this 2015-16 expedition on the National Geographic Orion, is recorded by our experiences and captures in digital images of whales, penguins, fur seals, icebergs, and dramatic scenery. For most of us, it was a trip of a lifetime.

The realization that we are truly in Shackleton's wake, almost exactly 100 years later, sends chills up my spine.

Whale Fluke and Zodiac, Humpback Whale, Paradise Bay, Antarctica.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/1000 sec; f/11; ISO 1250; + 0.67 EV)

Chinstrap Penguin goes for a Zodiac cruise, National Geographic Orion, Gold Harbor, South Georgia.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/1250 sec; f/11; ISO 640; - 0.33 EV)

A voyage to the white continent of Antarctica is a true expedition – enduring some of the world's worst weather. Conditions here will certainly put this lens through a tough test.

In addition to challenging weather, Antarctica and South Georgia is where some of the world's most spectacular wildlife and sculpted ice bergs are set against mind-blowing scenery. But to get there you must navigate Drake's Passage, crossing the turbulent waters of the Southern Ocean. Out there in the swells and wind-drven waves offers a great opportunity to photograph sea birds, including albatross, giant petrels, and a great variety of prions.

Light-mantled Albatross, Drake Passage, Southern Ocean, Antarctica.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/1600 sec; f/8; ISO 1600; + 1.33 EV)

Bracing myself along the ship's rail on the Cafe Deck, one by one black-browed albatross approach at eye level. Locking focus on a bird flying towards you requires continues (servo) focus model and a fast shutter speed to stop the motion. On a moving ship I'm going for shutter speeds 1/1000 sec and above, at ISOs ranging between 640 and 1600. If the light is fairly constant, I'll shoot in either Aperture or Shutter priority paying attention to shutter speed. If the background is changing between bright sky and dark water, I'll with to Manual Mode and meter off a middle tone, gray water, blue sky, or the deck of the ship. In Manual I can shoot with confidence with changing backgrounds.

Wandering Albatross soaring above Bay of Isles, Prion Island, South Georgia.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/2500 sec; f/8; ISO 1250; - 0.33 EV)

Right on cue, seabirds are following the ship. The seas are rolling and there's enough wind to blow the tops off the waves. Cape petrels dark across our wake like supersonic fighter jets. Also looming are albatross of several varieties. Most numersous are black-browed albatross, of which 70% on the Falkland Islands. The Holy Grail of birds in the Southern Hemisphere are the majestic wandering albatross, the largest bird flying bird in the world. Wanderer's nest primarily on South Georgia. We visited the Bay of Isles to photograph them in flight and on the nest, making a daring landing on Prion Island among the Fur Seals.

Lunge feeding Humpback Whale, Paradise Bay, Antarctica.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/1600 sec; f/8; ISO 1600; + 1.33 EV)

With the high ISO capability of modern DLR cameras I've been transitioning from heavy, prime lenses. At around 2 lbs., I love the freedom of the 100-400 zoom, hand-holding on moving platform, like on deck or from the Zodiacs. And, unlike the 70-300, it has a collar for working from a monopod or tripod. Ib my view, with the high-quality of image files of today's high resolution cameras, it's better to use a smaller zoom lens (cropping in post for the added reach), than to struggle with big glass.

Courtship Embrace, King Penguins, St. Andrews Bay, South Georgia.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/800 sec; f/11; ISO 1250; - 0.33 EV)

Experienced photographer's learn that there's a moment to every photographic situation, and those moments are fleeting. With albatross and other seabirds, the key moment when they tilt their wings, banking as they soar above the waves. Against the water, I use a single focal point to be sure I nail the focus and back-button-focus, so the camera is not trying to focus behind the waves.

Rockhopper Penguins brave the Surf Zone, New Island Nature Preserve, Falkland Islands.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/1250 sec; f/8; ISO 1600; Manual Exposure)

The White Continent of Antarctica is Earth's last great wilderness. There's no place that can compare in scale or beauty. The first time you go south is for the penguins and the wildlife. The second time, you go for the ice.

Polar fever, that unexplained longing for the ice, is real. It's Polar Fever that beckoned early explorers to return again and again, some ever to return. The legendary explorers – Amundsen, Scott, Mawson, Shackleton – and place names that will live forever – South Georgia, Stromness, Grytviken, Elephant Island, Cape Valentine, and Point Wild.

We are modern-day explorers from a different time, yet we have witnessed some of the same places as Shackleton and his men. For sure, an expedition for a lifetime and shared experiences I could never have imagined.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

From a Tango Hotel in Buenos Aires, Argentina

© Ralph Lee Hopkins.

All Rights Reserved. Worldwide.

Orangutans of Wild Borneo – Dispatch from Indonesia

Seeing the red apes of Borneo swinging through the canopy brings chills even at 95 degrees and 100% humidity. The sweat drips from my brow as I struggle to hold my camera steady. My ISO is cranked up to 2500 for a fast enough shutter speed in the dim light of the rainforest.

Young Male, Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), Camp Leakey, Tanjung Putin National Park, Borneo, Indonesia

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/500 sec; f/5.6; ISO 2500; -0.67 EV)

Peering between the beaches a young male is looking right at me. I frame the shot through the leaves naming the focus on his eyes. I'll never forget his eyes through my viewfinder, an instant connection with a primate that shares 97% of our DNA. This is a moment – looking into the eyes of a wild orangutan can change you forever.

Mother and Baby at Feeding Platform, Bornean Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), Camp Leakey, Tanjung Putin National Park, Borneo, Indonesia

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/400 sec; f/5.6; ISO 1600; -0.33 EV)

Hanging Out, Family in the canopy, Bornean Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), Camp Leakey, Tanjung Putin National Park, Borneo, Indonesia

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/400 sec; f/5.6; ISO 1600; -0.67 EV)

As if out of nowhere, a mother orangutan appears with two youngsters in tow. Very causiously, she navigates through the forest and approaches the feeding platform at Camp Leakey. She stuffs her mouth with bananas then climbs back into the canopy to eat in peace.

The wild orangutans of Borneo are endangered, with an estimated population of only 45,000 individuals remaining. If the rate deforestation and habit loss does not significantly decrease, Bornean orangutans are believed to be on the verge of extinction. The threats come from palm oil, pulp and paper plantations encroaching on the remaining lowland rainforest, along with illegal logging and poaching. Orangutan Foundation International, the non-profit organization founded by Dr. Kildikas, is working tirelessly to protect the remaining virgin forest around the National Park.

Camp Leaky was founded by Dr. Biruté Mary Galdikas as the base for her landmark studies over the past 4 decades. Although now wild, released orangutans return each day for a snack. Some clearly recognize Dr. Galdikas and approach closely, like old friends catching up on life.

Cute Couple, Proboscis Monkeys (Nasalis larvatus), Bako National Park, Sarawak, Borneo, Malaysia

Mother leaping with Baby, Silver Leaf Monkey (Trachypithecus cristatus), Bako National Park, Sarawak, Borneo, Malaysia

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/4000 sec; f/5.6; ISO 2500; +0.67 EV)

We experienced sweltering heat and refreshing rain showers. And we had moments, many of them, where the wildlife came close and seemed as curious about us as we were of them – like when a troop of crab-eating otlong-tailed macaques passed us on the boardwalk.

Mother carrying Baby, Long-tailed Macaque Monkey (Macaca fascicularis), Bako National Park, Sarawak, Borneo, Malaysia

(Canon EOS-1DX; 100-400mm; 1/400 sec; f/5.6; ISO 1600; -0.33EV)

Photographically, I find the tropics very difficult to capture. Challenges include fast moving animals, dappled light, complex backgrounds, and shooting through leaves and branches. Typically I carry two camera bodies, one with wide-angle zoom (Canon EOS-5D Mark III; 16-35mm or 24-105mm), and the other paired with a telephoto zoom (Canon EOS-1DX; 70-300mm). I use a sling-style camera bag for easy access but often switch to a backpack when carrying extra gear.

Coral Reef, National Geographic Orion, Pulau Lintang, Anambas Archipelago, Indonesia

(Canon EOS-5D Mark III; 1/250 sec; f/11; ISO 1250; -0.67 EV w/polarizer filter)

With today's low-noise digital cameras, I use high ISOs (up to 3200 or higher if necessary) for situations where fast shutter speeds are critical, like in dim light and shooting from moving boats. I use a single point focus for shooting animals though the leaves taking care to make sure the animal's eyes are in sharp focus. It's also important in the Tropics to always be prepared for rain and high humidity. Be sure to have lens clothes handy and a rain sleeve for you camera, and an umbrella for yourself. If possible, avoid storing your gear in air conditioned spaces so that lenses don't fog up with the change of temperature.

National Geographic Orion, Coconut Palm Tree, Fiji

(Sony DSC-RX 100M3, Fisheye 1/800 sec; f/5.6; IS0 800; -0.67 EV)

Moonrise at Twilight, South China Sea, Pulau Lintang, Anambas Archipelago, Indonesia

(Canon EOS-5D Mark III; 1/100 sec; f/8; ISO 2500; -0.67 EV)

Borneo and the Coral Triangle area of the South Pacific certainly demands more voyages in the future with Lindblad Expeditions and National Geographic. However for 2016, the National Geographic Orion will be heading to Europe, for exciting new itineraries from the Meditiranian to the Baltic Sea. To view the itineraries and for more information visit Expeditions.com.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

From Bali, Indonesia

© Ralph Lee Hopkins.

All Rights Reserved. Worldwide.

A Voyage from Bali to Fiji – Dispatch from the South Pacific

Indonesia is the world's largest archipelago, with over 18,000 islands stretching from Sumatra to New Guinea. This is one of the most tectonically active regions on Earth, where shifting tectonic plates form an arc of volcanic islands, each a unique tropical paradise unto itself. The islands of Indonesia are also one of the most beautiful places you will ever visit, and best explored by expedition ship sailing between the islands.

These images are from a series of voyages on board the National Geographic Orion. We embarked in Bali and sailed east, exploring the Spice Islands, continuing on to Australia, then New Guinea and the fabled islands of the South Pacific.

Boats at Sunrise, Komodo National Park, Indonesia.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 70-300mm; 1/500 sec; f/8; ISO 320; -0..33EV

Active Volcano, Larantuka, Indonesia.

(Canon EOS-5DmkIII; 24-105mm; 15 sec; f/4; ISO 400; 0.0EV)

Culturally, Indonesia has about 300 ethnic groups with traditions developed over the centuries with strong influences from Indian, Arabic, Chinese, and European sources. Traditional costumes and dances reveal aspects of Hindu culture and mythology. Indigenous cultures struggle to maintain traditional ways of life as cell phones and satellite television arrive to once remote villages. Change is coming, and fast.

Warrior, Alor Archipelago, Indonesia.

(Canon EOD-5DmkIII; 70-300mm; 1/80 sec; f/5.6; ISO 320; +0.33EV)

The biggest surprise of the voyage was exploring a remote corner of New Guinea, the coastline along the Bird's Head Peninsula to Triton Bay, with its unusual mushroom islands and karst formations. The rainforest coast was alive with wildlife and tropical birds, including the reclusive hornbills.

Mushroom Islands and Karst Formations, Triton Bay, New Guinea, Indonesia.

Australia's legendary Great Barrier Reef has some of the best snorkeling and diving anywhere in the world. There's another world beneath the waves. Pristine reefs with a kaleidoscope of corals and sponges paint the sea floor where colorful fish, sharks, and rays swim off into the deep.

Blue Coral Garden, World's best Snorkel Spot, Great Barrier Reef, Australia.

(Canon EOS-5DmkIII; 14mm; 1/800 sec; f/16; ISO 800; -0.67 EV)

Tropical Paradise, Dugout Canoe with Outrigger, The Blue Hole, Espiritu Santo Island, Vanuatu.

(Canon EOS 5D Mark III; 24-105mm; 1/200 sec; f/8; ISO 1250; -0.33 EV)

Sailing east to the Solomon Island and Vanuatu took us to WWII historic sites within a tropical paradise. The people make this part of the world compelling to visit. It's like going back in time, to a simper way of life with subsistence fishing and small farm plots.

Woman Fishing from Dugout Canoe, The Asmat Region, New Guinea, Indonesia.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 70-300mm; 1/800 sec; f/5.6; ISO 1250; -0.33 EV)

It's challenging photographing in the tropics with subjects both above and below the water. I find it's best to keep the camera gear simple. I carry two came bodies, one with wide-angle zoom (Canon EOS-5D Mark III; 16-35mm or 24-105mm), and the other paired with a telephoto zoom (Canon EOS-1DX; 70-300mm). I use a sling-style camera bag with easy access. With today's low-noise digital cameras, I often use high ISOs in situations where faster shutter speeds are critical, like in dim light and shooting from moving boats.

Child holding hands, Traditional Dress, Takpala Village, Alor Archipelago, Indonesia.

(Canon EOS-1DX; 70-300mm; 1/80 sec; f/8; IS0 640; -0.67 EV)

National Geographic Orion, Coconut Palm Tree, Fiji

(Canon EOS-5D Mark III, 16-35mm; 1/800 sec; f/22; IS0 320; -1.0 EV)

More and more I'm leaving the big guns in the bag, and instead shooting with my iPhone or small point and shoot. No matter what camera you travel with, you can learn more about both the technical and artistic sides of photography on a photography expedition with the National Geographic fleet operated by Lindblad Expeditions. The National Geographic Orion will be exploring the tropical waters from Borneo all the way to Easter Island again in 2015. To view the itineraries and for more information visit Expeditions.com.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

From a hammock in Fiji, South Pacific

© Ralph Lee Hopkins.

All Rights Reserved. Worldwide.

Ground Zero – Doors Off mission after Hurricane Odile 2014 – Dispatch from Baja California

With only a few days notice, we depart Tucson on Sunday morning, September 28, 2015. The sense of urgency comes from the timing, being only two-weeks after the strongest hurricane in history to hit Baja California. Hurricane Odile was a category 3 storm packing winds nearly 120 miles per hour walloping Cabo San Lucas and much of Baja California Sur. This was the storm I’ve been waiting for to document the changes in Baja’s coastline, with unfortunate consequences for poorly planned resorts and marinas built in harms way.

Sail boats beached by Hurricane Odile in La Paz Baja, Baja California, Mexico.

(Canon 1DX; 28-104mm; 1/2000 sec; f/8; ISO 640; -0.67 EV)

Looking North from the Sierra de la Giganta, Islas Danzante and Del Carmen, Baja California, Sea of Cortez, Mexico.

(Canon 1DX; 28-104mm; 1/2000 sec; f/8; ISO 640; -0.33 EV)

What surprised me the most is how wild the coast still remains. Following the mountainous shoreline along the Sea of Cortez we flew over bay after pristine bay. It’s a wilderness coastline with few roads because the terrain is just too rugged and unforgiving. Towns are few and far between. I'm also surprised by how green the peninsula is. In my 30 years of traveling in Baja I've never seen the desert so green. The coastline from Loreto south to the Cape region looks like a tropical rain forest.

Large lake high in the Sierra de la Giganta, Baja California, Mexico.

Flying over Los Cabos tourist corridor was deceiving. From the air it's difficult to appreciate the extent of the damage. But upon further inspection it was clear that all the hotels are ghost towns. All are abandoned except for cleanup crews and security. Normally you would see people crowding the courtyards and the pools. But there was no one. With windows blown out and no electricity or water, the 26,000 tourists who weathered the storm all took the first flights home from San Jose del Cabo. The airport has been closed for weeks to all incoming flights, since the control tower and terminals were all heavily damaged, requiring extensive repair.

Hurricane Impacts at Puerto Los Cabos, La Payita, San Jose del Cabo

(Canon 1DX; 28-104mm; 1/2000 sec; f/5.6; ISO 640; -0.33 EV)

Hotel development encroaches on the surf zone at Land's End, Baja California.

(Canon 1DX; 28-104mm; 1/2000 sec; f/8; ISO 640; -0.33 EV)

Perhaps most apparent from the air are the hotels at land end that suffered the most damage. The Solmar Hotel was hit the hardest. With its seawall located in the surf zone, it was only a matter of time that Mother Nature sent a reminder.

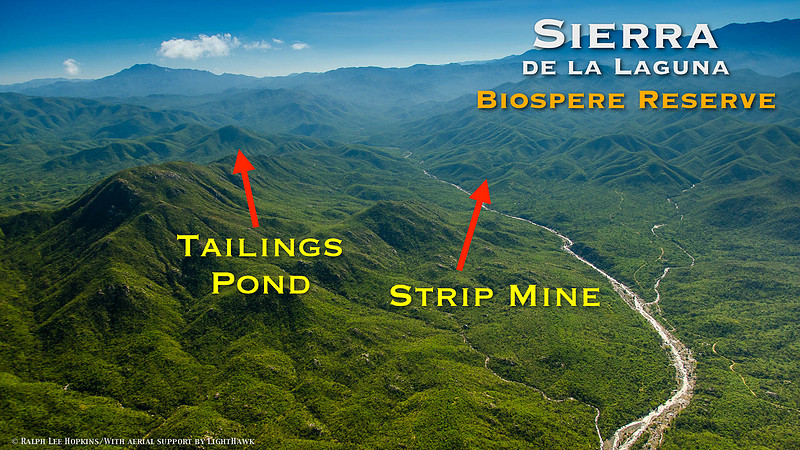

Proposed strip mine threatens an important watershed and potentially will pollute the aquifer

for La Paz and Todos Santos, Sierra de la Laguna, Biosphere Reserve.

(Canon 1DX; 28-104mm; 1/250 sec; f/0; ISO 640; -0.67 EV)

In a span of three days, we have flown 1700 nautical miles, captured 8000 geo-tagged frames, and shot 8 hours of video. These images will be added to the Baja Aerial Archive managed by the International League of Conservation Photographers (iLCP), and are available for scientists and conservation groups working to protect Baja’s wild coast and Sea of Cortez.

The hope is that we will learn from this storm and work to protect Baja's wild coast and offshore islands from future developments that negatively impact the fragile ecosystems.

Whale Sharks feeding in Bahia de los Angeles, Sea of Cortez, Baja California.

(Canon 1DX; 70-200mm; 1/2000 sec; f/5.6; ISO 1600; -1.0 EV)

This expedition was funded by the International Community Foundation, Packard Foundation, Mexican Fund for the Conservation of Nature, WildCoast, Resources Legacy Fund, and made possible by the LightHawk pilots of conservation.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

La Paz, Baja California, Mexico,

© Ralph Lee Hopkins.

All Rights Reserved. Worldwide.

Quest for the Northwest Passage – Dispatch from the Canadian Arctic

The mark of a true expedition is uncertainty. And in the Canadian High Arctic, any attempt to transit the Northwest Passage by ship is one of the most uncertain expeditions of all. Wind, weather, and ice conditions determine the exact course of any voyage through the Canadian Archipelago in the far north. These are the same treacherous straits and channels that foiled many historic expeditions, where dense, multi-year pack ice is jammed together making navigation difficult, if not impossible for wooden sailing ships back in the day.

Today, with climate change and shrinking ice conditions, the odds of transiting the Northwest Passage are better, but success is not guaranteed, even for a modern expedition ship with satellite-generated ice charts and forward scanning sonar. It is the ice that rules this world, and the reason we are here – to experience the frozen world of the Canadian High Arctic.

Heading north in Davis Strait toward Baffin Bay and Lancaster Sound at the entrance to the Northwest Passage, the National Geographic Explorer is framed perfectly through a giant ice arch along the west coast of Greenland.

Canon 1DX; 70-300mm; 100mm; 1/1250 sec; f/14; ISO 320; -0.67 EV

For this assignment on board the National Geographic Explorer, I’m outfitted with state-of-the-art Canon digital cameras from B&H PhotoVideo in New York, including two bodies ( Canon EOS 1DX and 5D MKIII), and an arsenal of L-series lenses from wide-angle (16-35mm, 24-105,mm) to medium and long telephoto zooms (70-300mm, 200-400 with its 1.4 extender built-in), and also the 100mm macro. For ultra-wide work, I’ve brought along a 14mm aspherical lens and 15mm fisheye. Add to this a monopod and tripod, Canon Powershot G12, and the GoPro 3+, and I’m ready for almost any situation. Bring on the ice…

“Ah, for just one time I would take the North-West Passage, to find the hand of Franklin reaching for the Beaufort Sea, and make a North-West Passage to the sea.” From a song by Stan Rogers

These immortal lyrics play over and over in my mind as the National Geographic Explorer navigates through the pack ice. Ahead of us, the Canadian Icebreaker, Pierre Radisson, cuts a swath for us to follow. It’s exhilarating to see what 13,000 horsepower can do in the ice, and thrilling to watch (and feel) us navigate in its wake.

Helicopter departs for sunrise survey of pack ice conditions, Canadian Icebreaker Pierre Radisson,

Fury and Hecla Strait, Northwest Passage, Canadian Arctic.

Canon 1DX; 70-300mm; 182mm; 1/800 sec; f/11; ISO 640; -0.67 EV

The quest for the Northwest Passage across through the Canadian Arctic archipelago eluded explorers for centuries. Names on the chart read like a who’s who in polar exploration, Franklin Strait, Larsen Sound, and the Parry Channel. Numerous expeditions were forced to over-winter, and some disappeared altogether – the most famous being the 1847-48 Franklin Expedition. Roald Amundsen was the first to successfully navigate the Northwest Passage in1903-1906. But it wasn’t until 1984 that the famous Lindblad Explorer (the world’s original expedition ship no longer afloat) became the first expedition ship to make the transit all the way to Barrow, Alaska.

Back in the moment, the National Geographic Explorer successfully navigates the swift currents and maelstroms of Belloit Strait. Tensions run high as we begin to encounter multi-year ice in Franklin Strait. Looking down from the bow, the ice is getting noticeably thicker with jumbled pressure ridges meters high. Ahead of us the icebreaker abruptly comes to a complete stop only a few ship lengths from our bow. With the pack ice quickly closing in, the National Geographic Explorer also comes to a halt.

The photographers among us brave the elements on deck to capture the close approaches of the icebreaker. Skilled maneuvering gets us going again, but we have now reversed our route. At this rate, the passage would take many days to complete, if at all. A decision is made to shift to Plan B, and instead explore north toward Ellesmere Island. Veteran travelers understand that good things happen when plans change.

Canadian Icebreaker Pierre Radisson and National Geographic Explorer, Franklin Strait, Northwest Passage, Canadian Arctic.

Canon 1DX; 16-35mm; 28mm; 1/500 sec; f/10; ISO 640; +1.67 EV

It’s a strange feeling to sit motionless in the thick pack ice. One can only imagine what it must have been like for Sir John Franklin and his men on board Erebus and Terror, the ships beset in the ice in 1847-48, a situation that ultimately took the lives of 128 men.

In stark contrast, we enjoy hot soup at lunch in the warm confines of the National Geographic Explorer, flagship of the Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic fleet. As perhaps the best expedition ship afloat for exploring the remote corners of our world, the ship’s ice-strengthened hull and bulbous bow can navigate through thick pack ice and past towering icebergs. It’s a very comfortable, if not luxurious, platform to experience and photograph the icy wilderness of the High Arctic.

The National Geographic Explorer sits motionless in the ice, her engines off, as we rest after a long day navigating in the pack ice. For the first time since coming on board over a month ago, the ship is silent.

Mother Polar Bear with second year Cubs on Pack Ice, Lancaster Sound, Northwest Passage, Canadian Arctic.

Canon EOS-1DX; 200-400mm; 560mm w/1.4X; 1/800 sec; f/16; ISO 1250; +1.67 EV

It happened just before midnight – a young male polar bear approaches the ship’s bow. In a complete state of awe, a handful of us gaze down from the bow as the curious ice bear investigates the strange object that has entered its world. Not many ships travel these waters, so there’s a good chance we’re the first ship this bear has ever seen. As if in slow motion, this top predator of the Arctic walks the length of the ship past the stern, then jumps between ice floes and disappears back into its white world.

Curious Polar Bear stands at the Bow of the National Geographic Explorer, Northwest Passage, Canadian Arctic.

Canon 5DMKIII; EF16-35mm; 16mm; 1/800 sec; f/16; ISO 1250; +0.67 EV

There’s a strange attraction to being in the pack ice, looking out over vast expanses of frozen ocean with hope of discovering a polar bear in its natural habitat. It’s called “Polar Fever.” And I’ve got it bad, traveling to the polar region year after year. In a melting world each and every polar bear sighting is especially meaningful. Like ours, their world is rapidly changing.

In expedition travel there’s always something new to see or discover. For the first time in my 25 years in the far north, we are treated to a brilliant display of the Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis). Although always a possibility late in the season (when it starts getting dark), seeing the Aurora is a rare treat. The bright dancing lights seen above the magnetic poles are created from collisions between electrically charged particles from the sun as they enter the earth’s atmosphere. Reportedly, solar pulses from the sun this fall are extremely strong, painting the sky a neon green reflecting in an amazingly calm ocean.

Northern Lights reflect in a unusually calm seain Foxe Basin near Baffin Island, Canadian Arctic.

Canon 5DMKIII; 16-35mm; 16mm; 1.6 sec; f/2.8; ISO 3200; 0.0 EV

Photographing the Northern Lights from a moving ship is no easy task, and possible only since the advent of high ISO settings on modern digital cameras. So what should my settings be? Being one of the lowest noise cameras on the market, I cranked my Canon 5DMKIII up to ISO 3200. Workable shutter speeds, around 1-3 seconds, were attained by using a wide-angle 16-35mm/f2.8 lens. The calm sea conditions also permitted the use of a tripod, something I would not normally try on a moving ship. For some shots, I simply braced the camera on the ship’s rail using a neck-rest, something I always travel with. And finally, since autofocus does not work effectively in the dark, I manually pre-focused to infinity and locked focus with gaffer’s tape.

Melting Ice, Window thru Iceberg, Sunburst, Eclipse Harbor, Boothia Peninsula, Canadian Arctic.

Canon 5D MKIII; 16-35mm; 16mm; 1/640 sec; f/22; ISO 320; -1.0 EV

Homeward bound and looking down from 35,000 feet on the Canadian landscape and recounting all the sightings and experiences, I realize the memories from the past 6 weeks will last a lifetime. Although we never did make it through the point of no return, the quest to transit the Northwest Passage has been a true expedition in every sense of the word – from the pack ice and Canadian Icebreaker, to polar bears and walrus, and the aurora borealis. There were surprises, and some disappointments. In the Arctic, as in life, you can make a plan but you can’t plan the results. Stay true to the moment and great things will happen. Bring on the ice…

Ralph Lee Hopkins

St.Johns, Newfoundland

PS – I'm already looking forward to next summer's voyages Exploring Greenland and the Canadian High Arctic, July-August 2015.

© Ralph Lee Hopkins

Kimberley Tapestries of Stone – Dispatch from Australia's Wild Northwest

Imagine a coastline with cliffs of red sandstone rising above an azure sea. A white-bellied sea eagle circles overhead then swoops down, landing on its nest perched high on a cliff. Imagine a land so remote that indigienous people still roam the canyons and fish its shores. They are the guardians of rock art panels scattered far and wide across the region, some dating back more than 40,000 years, others possibly as old as 100,000 years. These enigmatic paintings of red ochre are carefully hidden under overhangs, protected by a case hardening of silica weathered from the ancient layers of stone. Like Tapestries of Stone, their origins are still being debated today. Each rock art panel is a masterpiece onto itself, and worthy of careful study and deep contemplation.

An elegant human figure pictograph hidden beneath a large sandstone boulder.

Imagine a land so wild that few Australians have visited its hidden waterfalls and deeply eroded canyons. You're tempted to swim from the perfect sandy beaches but fear crocs may be lurking. Imagine a place so different that it's simply referred to as The Kimberley, and considered by some – Australia's last frontier.

The National Geographic Orion anchored at Hunter River, Kimberley Region, Australia.

An assignment with Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic on the National Geographic Orion brought me to this landscape of rock, sea, and sky. We spent timeless days exploring remote canyons and mangrove-lined channels cut deeply into the Kimberley Plateau. Places like Porosus Creek along the Hunter River, where saltwater crocodiles, or "salties," are found basking on mud banks at low tide. Another day found us exploring the rocky shores of Talbot Bay, where mega-tides over 10 meters (30 feet) cause strong tidal currents. Where the seawater rushes though tight passages in the rock formations, dangerous maelstroms form, called the "Horizontal Waterfalls." We also explored the far reaches of the King George River Canyon, where twin 80 meter high waterfalls cascade from the rim, and visited Montgomery Reef, the largest inshore reef complex in Australia. The locations were as diverse as they were spectacular, and each day revealed many surprises, as expedition days often do.

Saltwater Crocodiles are one of the planets oldest predators, with fossils dating back to when dinosaurs roamed the earth almost 100 million years ago.

It's a quirk of geologic fate that the ancient Precambrian sandstone formations of the Kimberley Plateau remain undeformed, surviving nearly 2 billion years of turmoil. On the underside of boulders are perfectly preserved ripple marks that appear as if the sand was swept by currents only yesterday. Almost everywhere else on earth, rock layers this old – including the contorted schist and gneiss in the bottom of Arizona's Grand Canyon – have been heated, folded, twisted and changed beyond recognition from their original form, a process called metamorphism. It boggles the mind that through time this region, known to geologists as the Kimberley Craton, has been a virtual life raft in a sea of turbulent plate tectonics.

A Rock Wallaby sits motionless under a rock overhang.

The sandstone formations of the Kimberley were deposited 1.8 billion years ago in a shallow marine basin bounded by steep mountain ranges uplifted along active fault zones, where plate tectonic collisions were assembling new continents. With repeated collisions and rifting events the Kimberley ultimately became attached to the ancient supercontinent Gondwanaland, connected to what would later become Antarctica. Venture to the margins of the Kimberley Plateau, along the Halls Creek and King Leopold fault and thrust zones, and you'll see firsthand the deformation that occurred along its boundaries during a long, turbulent history. Exposed in dramatic fashion along the rocky coast, sandstone layers are bent into anticlines and synclines, thrusted upward along faults until the layers are standing on end, and overturned along steep limbs of major geologic structures.

Repeated collisions over time have warped sandstone layers downward into a syncline.

Stained red by the oxidation of iron over the eons, the Warton, Pentacost, King Leopold sandstones have been sculpted by erosion for nearly the past 50 million years since the rifting and separation from Antarctica, creating rocky cliffs, overhangs, and hidden caves that became the stone tapestries for the rock art paintings made long ago. Meanwhile, sand grains are plucked from the rock grain by grain, and washed seaward to become a beach once again, after being locked away in the rocks for almost 2 billion years.

Layers of sandstone reflect golden light and blue sky below King George Falls.

Perhaps the biggest surprise about the Kimberley region are the Aboriginal people who still live here, their impressive and mysterious artwork, and the ongoing importance of wandjina spirits in their dream world. Paintings of extinct megafauna, like the carnivorous marsupial Thylacoleo, point to an ancient civilization that stretched across the Kimberly region, pushed south by the Ice Age, migrating from Africa to Indonesia when sea level was 140 m lower. During this time the coastline was 400 km further to the northwest, making it possible to literally walk to Australia from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Not coincidentally, a single species of boab tree (Andonsonia gregorii) came along with them, its stock linked to a common ancestor in Africa. The geographic distribution of boab trees overlaps almost perfectly with known rock art locations. Rich in vitamin C, the trees have many medicinal properties and uses in daily life, and the nutritious fruit lasts more than a year, making it perfect for travel.

Hand stencils and human rock art figure overlap on sandstone tapestry.

Red mangrove seedling takes hold in a rock crevice against a backdrop of honeycomb weathering.

The month-long assignment was capped off by a thrilling "doors-off" helicopter ride to Mitchell Falls and overflight of the ship underway, with the Zodiacs exploring a literal maze of mangrove channels. I used a 24-105mm image-stabilized lens and cranked up the ISO to keep shutter speeds over 1/1000 second. Being the newest ship in the Lindblad-National Geographic fleet, it was important for the assignment to capture the National Geographic Orion from the air, in it's true expedition mode juxtaposed against blue-green water and colorful sandstone cliffs.

Aerial photo of a Zodiac being approached by a salt water crocodile.

Flying back across the Pacific Ocean to North America, the last month now seems like a dream. With my eyes closed the rock art comes alive with visions of dance, ceremony, and ritual. Perhaps it's no coincidence along these rocky shores exists the largest population of Humpback Whales, who return from their feeding waters in Antarctic to mate and give birth. If the land is this rich with rock art above today's sea level, then think what it must have been like during glacial times, when stone canyons reached like fingers to the coast. Imagine the secrets hidden from view beneath the sea. Imagine the Kimberley.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

June 30, 2014

Melborne, Australia

© Ralph Lee Hopkins

2014 Colorado River Photo Expedition – Dispatch from Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, USA

A river trip down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon is one of life's great adventures. Looking down from the rim it's hard to comprehend how vast the Grand Canyon really is. From the river, you discover the Grand Canyon is not just one canyon, but made of canyons within canyons within canyons. And many have flowing water and waterfalls emerging from springs in the canyon walls. Around every twist and turn, there are hidden canyons of all kinds, from box canyons to slot canyons, and best accessed from the river.

White-water action in Hermit Rapid, Granite Gorge

Every other year I team with my good friends at Arizona Raft Adventures for a two-week photo expedition. The 2014 was led by Grand Canyon legendary boatman and photographer, Dave Edwards. With over 150 river expeditions through the Grand Canyon, it's equivalent to spending more than 6 years on the river – below the rim, in all seasons, all kinds of weather. Along with him were five professional guides, all responsible for navigating oar-powered rafts down 226 river miles through 150 named rapids.

Reflections and River Rocks, Conquistidor Aisle

The Grand Canyon will humble you, by challenging your perception with it's immensity – it's over a mile deep, over 18 miles wide, and 277 miles long. All the empty space is capable of holding all the world's river water and still only be half full. In it's depths there are canyons within canyons. Place names like Vassey's Paradize, Elve's Chasm, Deer Creek, Blacktail and Matkatamiba Canyons.

River camp under Tapeats Sandstone ledges, Lower Granite Gorge

The Grand Canyon is one of the hardest environments to do photography. First, there's the water. On the river you face water like you've never seen before, breaking waves that will knock the breath out of you. And sand. To understand the conditions you will face, dump a pile of sand in your back yard, set up your tent, throw a few shovels full inside, and turn on a strong fan to blow it around into every nook and cranny. Both are certain death to digital cameras without precautions.

Flute river rock, sculpted Redwall Limestone, Lower Granite Gorge

Upper Falls over steps of Tapeats Sandstone, Deer Creek Narrows

The experience of being on the river is hard to explain. After a couple of days everything seems to be moving in slow motion, mirroring the pace of the river, the rhythmic beats of the oars setting the pace. As your mind becomes quiet, thoughts even slow down, and you start recalling memories of things you haven't thought about in years. Your body adjusts to the cycle of the sun, in bed by dark and up at first light with the melodious song of the Canyon Wren.

Upper Falls, Tapeats Sandstone, Deer Creek Narrows

Sleeping under the stars reunites you with the universe, and grounds you here on earth. To see the North Star and the Big Dipper through a sliver of sky between towering cliffs, beckons you to ponder the origins of all things, and marvel at the mysteries hidden in the rocks. It's interesting to learn that the age of the Grand Canyon is still being debated to this day. In a subtle but profound way, the Canyon changes you.

The next Colorado River Photo Expedition is already being planned for May 2016. Contact Arizona Raft Adventures for more information.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

May 15, 2014

Flagstaff, Arizona

© Ralph Lee Hopkins

Remarkable Journey – Dispatch from Baja California, Mexico

It was a month on the water like few others. From the friendly whale lagoons of Magdalena Bay, to water-level views of pilot Whales. A rare sighting of a great white shark feeding on a dead sperm whale, to sperm whales swimming under the bow of the National Geographic Sea Bird. Perhaps the most amazing sighting of all were the killer whales swimming along side the ship in the moon light, if not for the bioluminescent dolphins almost as a nightly occurrence. This is why we come to Baja California and the legendary Sea of Cortez.

The best thing about an expedition is the element of surprise.

Around midnight on the National Geographic Sea Bird, our Hotel Manager, Erasmo, and Chef, Eric, were out looking at the moon on the fantail, the lowest deck at the stern of the vessel where we load Zodiacs. Sailing in San Jose Channel along the Baja Peninsula, the sea was flat calm, reflecting not only the moon, but each and every star and several planets too.

Then, as if in a dream, a large male killer whale leaped from the water and looked them in the eye, it’s six-foot tall dorsal fin towering above them and reflecting in the moon light. “It was the most amazing thing ever,” said Erasmo, “I could have touched the whale, but instead my instinct was to pull Eric back from the rail. The animal was that close!”

The Bridge was informed that the ship was being followed. Expedition Leader, Sue Perin, woke up all the guests. The killer whales, of course, were simply curious, checking out the ship and making several very close passes under the bow, rolling on their side looking up as us. For more than an hour, a small pod of five whales swam along side. In complete awe, when we couldn’t see them, we could here their forceful blows echoing off the flat calm water.

Although a third of the world’s cetaceans are known to visit the Sea of Cortez, sightings of killer whales are relatively rare. For everyone, seeing whales in the moonlight was a dream come true. Even today’s modern digital cameras have troubling handling dim moon light from a moving ship. I shot a few frames with the ISO cranked up to 25,000 at a shutter speed of ¼ second, good enough to make a couple of images to document this most unusual experience – whale watching under the full moon.

Little did we know at the time, the killer whale sighting was just a very early start to what would prove to be a very long and amazing day. Just after sunrise we encountered a huge pod of long-beaked common dolphins feeding along Isla del Carmen within Loreto Bay National Park. For more than an hour before breakfast, the ship cruised slowly with a few hundreds animals darting in all directions, bursting together in small teams, and making impressive leaps above the surface. After breakfast, Senior Deckhand, Clem, spotted a lone humpback whale whale which swam circles around the ship, making short dives, surfacing again and again at very close range. With each dive, this 40-ton animal would raise its fluke, eliciting cheers from the crowd assembled on the bow.

After lunch we enjoyed a busy afternoon of watersports, kayaking and snorkeling in Bahia San Juanico along the Baja Peninsula. After short sunset walks, the ship’s crew treated us to dinner on shore with the full moon rising over the National Geographic Sea Bird anchored in the bay. But the day still wasn’t complete, as a few of us still had enough energy to stay up or wake up to catch a glimpse of the total lunar eclipse.

Killer whales in the moonlight, hundreds of dolphins feeding around the ship, a humpback whale circling the ship, kayaking and snorkeling along a rocky coastline, sunset walks, a rising full moon over the Sea of Cortez, and a total lunar eclipse… For those who were here to experience the magic, today will simply be remembered as one of the best days ever!

National Geographic Sea Bird, Baja California, Mexico

<First appeared as a Daily Expedition Report, Expeditions.com>

Whale Tales Maui – Dispatch from the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary

We casted off from the Mala Ramp in Lahaina just before sunrise. Clouds on the far horizon hid the full moon, snuffing out any hopes of a breach against the moon at sunrise. The morning started off slow. We encountered mom's with calf and escort in tow, breath holders disappearing for another deep dive, and a worn out competitive pod taking a breather.

Conditions were ideal for crossing the Pailolo Channel towards Molakai. Everything changed at 7:16 am with the first breach. A whale's first breach often is the highest, and this one was an acrobatic display with the tale fluke almost clearing the water line. Taken by surprise, we all missed it. Luckily it happened over and over again, as a small competitive group of whales breached twenty times or more, while chasing a female playing hard to get, no doubt. Or could it have been the full moon? It's still anyone's best guest why whales breach.

As photographers, we dream of repetitive behavior, and that's exactly what happened. For the next 58 minutes there were at least 20 breaches, about one every 3 minutes according to the metadata recorded in the photos. Working from a small boat it's easy to shoot both above and below the water, dipping the underwater housing over the side in situations where the whales approach us. For action above water, I use my 70-300 zoom on a Canon 1DX with it's blazing fast 10 frames per second. Below water where things happen more slowly, I use a 14mm fish-eye lens on a Canon 5D Mk 111 in a Ikelite dome port housing.

Each winter, humpback whales swim 2500 miles from their feeding waters in Alaska all the way to the Hawaii Islands to breed and raise their young. From around November-December and on into March-April, it's a gathering of whales in the warm protected waters off Maui like few places on earth.

What I love about observing and photographing the whales is the mystery – so much remains unknown about their life and behavior. The most fascinating behavior of all is when a pair of whales become curious, briefly adopting our boat, spy hoping for a closer look. It's anyone's guess what they're thinking, but it's no mystery that they are checking us out, and from very close range. A dream come true...

One thing is for sure, during the courtship and mating seasons it's a dance of grace and beauty punctuated by moments of power and aggression. Somehow it works, as the whales are doing well and increasing in numbers by about 7% a year. In fact, the North Pacific population is believed to have recovered to pre-whaling numbers exceeding 20,000 animals, good news and a conservation success story.

And each year whale researchers and whale lovers also gather in Maui for the annual WHALE TALES event, organized by Whale Trust Maui to help raise money for ongoing research about the lives of these magnificent air-breathing marine mammals. A popular item in the silent auction was a trip with Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic on board the National Geographic Sea Bird to Southeast Alaska to visit the Hawaiian humpback whales in their summer feeding waters.

This year's presenters included Whale Trust co-founder and National Geographic photographer, Flip Nicklin, filmmakers Howard and Michele Hall and Jason Sturges, and a who's who in whale research and conservation including Jim Darling, Ed Lyman, Fred Sharpe, Robin Baird, and local photographers Marty Wolfe and Douglas Hoffman.

Don't miss the next Whale Tales event in February 2015. And to visit the Hawaiian humpbacks in Southeast Alaska, check the expeditions offered by Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic.

Ralph Lee Hopkins, Lahaina, Hawaii

© Ralph Lee Hopkins

Each year in December I travel to Tucson for a photography workshop with National Geographic Expeditions. The workshop is hosted at the beautiful, and very relaxing, Miraval Resort, the perfect location to explore creativity and being in the moment.

The photographer's mantra – LIGHT, COMPOSITION, and MOMENT– is taken to a new level with the addition of the word SPA.

Photographer's choose a workshop of many different reasons, but learning to be more creative usually ranks high. And creativity starts with passion. Discovering your passion takes your photography to the next level. Create a project and see it through. It might all start with a workshop.

Students in the workshop mix photography with SPA treatments, a very enjoyable way to be in the moment and learn to see the world in a new way. Photographic assignments visit nearby locations, including Catalina State Park and Purple Sage Ranch. Field shoots are followed by classroom sessions and image critiques.

The highlight of the weekend workshop is having the opportunity to photograph Tony Redhouse, a native American musician and healer who performs original music combined with traditional dance. Truly an honor and always a powerful experience.

Looking forward to returning to Miraval again next year December 4-7, 2014.

Ralph Lee Hopkins, Tucson, Arizona

Iguazú Falls and the Euphoria of Falling Ions – Dispatch from Argentina

We all have felt the euphoria – the feeling of well-being when walking along a beach with crashing surf, or around waterfalls with thundering cascades, or raging white-water rivers. The effect is created by invisible molecules of air – called ions.

It’s a well-known fact that breathing ions – specifically the negatively charges ones – produce biochemical reactions in the human body that increase levels of the mood-altering chemical serotonin. In nature, negative ions are created as air molecules break apart around moving air and flowing water. Air circulating in mountains, pounding surf, and large waterfalls all contain elevated levels of negative ions. In fact, many air purifiers claim to release negative ions into the room, promoting their positive health effects.

It’s hard to feel tired or depressed near waterfalls, and we found this to be true at Iguazú Falls along the border of Argentina with Brazil. Iguazú Falls forms the widest set of cascades anywhere in the world, being taller (240ft/80m) and more than twice as wide as Niagra Falls (1.8mi/3km). The cascades and the surrounding sub-tropical Atlantic Rain Forest are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a hot spot for bio-diversity, with over 400 species of birds and many endemic plants and trees.

It's counter-intuitive that it's the negative ions bring about positive side effects of being in nature. The act of breathing pure, super-charged molecules of air helps lower stress levels and create a sense of well-being. These effects can also help your photography, enhancing creativity and helping to be more focused on the present moment.

These images here were made on a two-day extension to Iguazú Falls National Park in Argentina with Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic.

Required equipment for shooting waterfalls includes a sturdy tripod, polarizing filter, neutral-density filter (4-stop or Variable), graduated-ND filter (2-stop/soft-edge). These images were made with a Canon EOS 1DX, 16-35mm. 24-105mm, 70-300mm and Singh-Ray filters, all from B&H PhotoVideo. Be sure to experiment, varying shutter speeds and playing with different depth-of-fields by adjusting the aperture.

Our visit to the cascades in the rain forest was a fitting culmination to an expedition that took us Ushuaia across the Southern Ocean to the Falkland Islands (Malvinas), South Georgia Island, Orkney Island, and the White Continent of Antarctica.

Re-entry into the modern world after spending time in wild places is always challenging, so what better way to ease the stress than with a blissful visit to the more than 250 waterfalls found at Iguazú. Feel the euphoria and photograph what you feel.

Safe travels, always.

Ralph Lee Hopkins, Buenos Aires, Argentina

It is about the Camera! – Dispatch from Africa with the Canon EOS 1DX and Canon 200-400 Zoom

For me it's never been about the camera, really. I've gone from 4 x 5 to medium-format, then on to 35mm film, and finally digital. Each camera system has had advantages and challenges. But it all comes back to image – finding the light, making a great composition, then waiting for the moment.

However, the truth is today with modern digital cameras, it is about the camera!

My recent experience in Africa with Canon's flagship Canon EOS 1DX paired with the new 200-400 telephoto zoom has changed the way I shoot. The camera body is from B&H photo and the lens was rented from LensProToGo.com. I put the equipment through some rigorous situations and found the lens to be tack sharp and the camera focuses quickly and accurately, easily the best camera-lens combination I've ever used in my 30 year career.

The leopard was spotted at 7:05 am, only about 15 minutes out from Savuti Camp in Botswana, along a channel located between the Chobe River and the Okavango Desert. Frame #1 was the safety shot, a bullseye composition as she came down off a termite mound.

Over the course of the next 4 hours, I would shoot 1285 frames as we followed her as she hunted impala. She became know to everyone in our group as "Cindy Crawford" because she was a Super Model, climbing two trees, three termite mounds, and walked past the perfect reflecting pool. At one point we even waited for over 2 hours until she came down from resting in a tree. Only photographers are this patient...

With affordable 32 GB flash cards and 2TB hard drives, the number of images is only limited by your imagination. I'm always ready for action, so I set the camera in Apertue Priority, AI Servo focus, and high burst mode, which is 10 frames per second. Anticipating the moment, I shoot in short bursts to give myself the choice of the best frame.

The new Canon 200-400 telephoto zoom allows for far more freedom and improved compositions. Being able to zoom in with a flick of a switch to 560 mm using the built-in 1.4x teleconverter has changed everything. No longer do you have to disconnect the lens from the camera in the field to attach the teleconverter, saving valuable time in critical moments and also helps minimize sensor dust. Then, when the animals approach, you can flip back to 1x and zoom out to 200mm.

Having a disciplined workflow is important for staying organized while on the go. Back in camp, I download images immediately into two external hard drives, one which is the backup vault, the other my working catalog. I do a quick edit deleting obvious mistakes and near-frames. In fact, I delete a relatively high percentage of the images in the working catalog using Photo Mechanic, before importing into a Lightroom for processing.

The truth be told, in today's digital world, it really is about the camera. With high-end DSLRs, I no longer worry about image quality or noise at high ISOs and think nothing about cranking it to 1600 or beyond to get the shot. And with high frame-rate shooting, I'm confident that I'll capture the action. Sure, shooting over a thousand images over 4 hours means I've got some editing to do, but I'm much happier deleting images knowing I've nailed the shot.

Scrolling Slideshow

One Picture – Baja California at Sunrise

Canon 5D MkIII, 16-35mm @ f/22, 2 seconds, SinghRay 2-stop Soft-step Grad ND, Induro Tripod and Ballhead

For everyone who attended this year's Baja Land & Sea Photo Retreat they will never forget the sunrise along the wild shores of the Sea of Cortez. Even those that slept through it heard about it. It had all the potential of just another cliché sunrise. But with each passing moment it became more and more unreal, until it was over the top.

My eye was drawn to the reflections on the wet rocks and motion of the surf. I set up my tripod as close to the rocks that I dared. The sturdy Induro tripod and ballhead made it easy to stabilize the camera in a tenuous situation. I'm after foreground that adds a sense of place, depth, or drama to the image. Sometimes the motion is too much, the water lost in the cotton-candy look. Other times not enough, looking stiff and streaky. To get it just right takes practice and experimentation. Even then it's in the eye of the beholder.

I shot through a sequence of exposures varying my f/stops from f/2.8 to f/22 to alter the depth-of-field, changing ISO to control shutter speeds between 1/4 and 2 seconds, with a neutral-denisty filter used to hold back the intense sky. Sometimes we get seduced by the filters when software might achieve a better result, so always shoot with and without filters so you can make the choice later.

The high-ISO capability of the Canon 5D MKIII is superb. I always use the lowest ISO possible for the desired result, but I don't hesitate cranking it up to 1600 ISO, if that what it takes to get the shot. The RAW image was processed in Lightroom for color balance and saturation, which was held back because of the naturally intense colors. Noise reduction was applied to the final image. The selected frame had the best reflections combined with the velvety motion of the water.

What I love about nature photography is that it forces you to be in the moment out in the wilds – to be mindful enough to wait for the light, fine-tune the composition, and anticipate the action. The magic is when it all comes together in the viewfinder, then "click." We filled our memory cards with memories that will last forever...

Click here for information about the January 11-18, 2014 Baja Land & Sea Photo Retreat with Flip NIcklin and our friends from B&H Photo.

Baja Land & Sea – Scrolling Slideshow

Scrolling Slideshow – COLOR

Autumn at Camp Denali – Dispatch from Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska

It’s like a dream looking out the window from Camp Denali at Mount McKinley, North America’s tallest peak at 20,320 feet above sea level. I’m warm and snug in a log cabin with a wood fire burning. The mountain is an impressive mass of solid rock and ice. The Athabaskan people call the mountain Denali – meaning simply, the High One – rising abruptly 18,000 feet above the surrounding countryside, more vertical relief than any mountain anywhere in the world.

Clouds come and go all day, providing peak-a-boo views of the mountain. From where I sit, just over 30 miles from it’s base across the McKinley River, Pioneer Ridge is visible as it climbs toward Denali’s North Peak, casting a shadow on the Wickersham Wall, a climber’s nightmare. The mountain makes it’s own weather and reveals itself less than fifty-percent of the time. I know this from personal experience, as it took me three visits to the park to see the top of the mountain.

The rustic cabins and lodge at Camp Denali are 90 miles from the park entrance, near the far end of the winding, un-paved park road. I’m here by special invitation as the photographer-in-residence, teaching photography while searching the tundra looking for wildlife and scenic landscapes. You don’t have to go far – compositions are everywhere. We visit some of the locations made famous by Ansel Adams, including Reflection Pond and Blueberry Ridge overlooking Wonder Lake. When the mountain is out, concentrate on the mountain.

A wilderness area larger than the state of Massachusetts surrounds us. It’s not uncommon for bears, moose, and even wolves to wander through camp. We see them all during our day trips along the park road back towards the Toklat River. Bull moose wade in the kettle ponds, caribou graze the tundra, grizzly bears lap up berries like there is no tomorrow, and red fox hunt arctic ground squirrels oblivious to our presence. We even encounter two wolves, one with a radio-collar, not far from the road. Meanwhile Dall sheep graze the mountain ridges high above us, appearing as tiny white dots easily visible against the dark volcanic rocks.

Fireweed is a sure sign that fall is on the way. Autumn comes early this far north. At 63˚ above the equator, Denali is just south of the Arctic Circle. The color seems to change by the hour, providing interesting macro subjects with water drops clinging to every leaf and berry. Willow, birch, and aspen trees turn yellow, while ground-hugging bearberry and blueberry bushes paint the tundra with brilliant reds and burnt orange.

Overnight the snowline drops another 1000 feet. A cold rain and hard frost in camp accelerates the changing season. Two weeks from now Camp Denali will be buttoned-up for the cold, dark winter.

I place another log on the wood stove, pour a glass of red wine and look up at the mountain. Humbled by its wildness, I’m convinced this is one of the best views in the world. I promise myself I’ll return to Denali to spend more time in the shadow of the High One.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

Camp Denali

September 5, 2014

Arctic Quest – Dispatch from Greenland and Baffin Island

Arctic Quest, a voyage exploring the High Arctic on board the National Geographic Explorer with Lindblad Expeditions. We departed Reykjavik, Iceland on July 22, 2013, sailed across the Denmark Strait to southern Greenland, north along the coast to Ilulissat, then across the Davis Strait to Baffin Island and Devon Island in the far north. When traveling I'm always on assignment to photograph the day-to-day expedition and also the ship set against the arctic landscape. Taking advantage of unusual calm weather and favorable ice conditions at Disko Bay, we chartered flight-seeing planes and also a helicopter to shoot aerial photos of the Explorer as she navigated the pack ice.

Check out this short video by Jim Napoli

When you look at a globe of our planet, the Arctic Ocean appears as a vast expanse of mostly frozen seawater. This ice-choked ocean of icebergs and pack-ice is surrounded on all sides by a landscape of glacially-carved bays and fjords, cut by just a few significant passages, each of which are critical for the circulation of ocean currents. The landscape is mostly frost-shattered rock and boggy tundra, with trees only inches tall, and carpets of miniature wildflowers that bloom for only a short time in summer under the ephemeral warmth of the midnight sun.

Standing out like a small continent in the high arctic is Greenland, the world’s largest island. More than 80% of Greenland is covered by a rapidly melting icecap, the second largest accumulation of ice after Antarctica. To the west across Baffin Bay and the Davis Strait is Baffin Island, with its dramatic fjords geologically similar to Greenland separated by plate tectonics during the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean over the past 140 million years.

The ice fjord of Illulissat, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is where the world’s fastest moving glacier, Jakobshaven, is calving the greatest amount of ice anywhere on earth. If you’ve seen the documentary Chasing Ice by National Geographic photographer James Balog, this was the glacier captured on film calving an iceberg the size of Manhattan. Mountains and castles of ice on a scale seen only in the Antarctic, are stranded along the end moraine at the entrance to the fjord, each berg a unique sculpture and work of art. Amazingly, the icebergs are more than 40 miles from the glacier face.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the trip was exploring the east coast of Baffin Island, the worlds 5th largest island. Exploring new territory we encountered a number of curious polar bears or Ice Bears – symbol of the arctic. Our polar bear encounters could not have been more diverse, with all kinds of behavior including several that approached the ship. There were pure white bears, yellow bears, young bears, all appearing very fat and healthy.

We also encountered whales, including the mythical narwhals. We also encountered with more than a dozen endangered bowhead whales that, at one point, surrounded the ship. Bowheads are a true arctic species hunted by man for more than a thousand years, from the highly-skilled Thule culture followed by the Inuit people and later the Vikings. The advent of the harpoon gun employed by European whalers almost drove these gigantic cetaceans to extinction, driving numbers into the 100s. Bowheads can reach more than 65 feet in length, approaching 100 tons in girth, and yielded 30 tons of oil per animal, highly lucrative in its day. Thankfully, with protection, these whales are making a comeback, with latest census numbers yielding more than 20,000 animals. We can only hope the trend continues.

All of us on board the National Geographic Explorer – from the ship’s officers, crew, expedition staff, and seasoned travelers – agreed that this was one of the most spectacular, and meaningful, voyages in recent memory. An experience highlighted by the young male polar bear that swam directly across our bow, looking each one of us in the eye. We could see his front paws paddling through the crystal clear arctic water, as he swam from one ice floe to another, showing no fear, only curiosity about this blue ship with the yellow stripe.

For a timeless moment I experienced a personal connection with the true symbol of the arctic – the Ice Bear – that I will never forget.

Ralph Lee Hopkins

Baffin Island, National Geographic Explorer

________________________________________________________________________________________________

The National Geographic Explorer is the flagship of the Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic fleet and, with it's ice-strengthened hull, is the best expedition ship afloat for exploring the remote corners of our world. The Explorer is a very comfortable, if not luxurious, platform to experience and photograph the wilderness in the high arctic. Experienced Ice Captains navigate tuncharted waters using state-of-the-art forward scanning sonar. Technology and experience will be put to the test on next summer's transit of the Northwest Passage. <For information click www.expeditions.com>

The Last Paradise – Dispatch from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

Here in the new Galapagos Airport on Baltra Island I’m reminded just how remote the Galapagos Islands really are. I’m returning from a series of photography expeditions with Lindblad Expeditions on board the National Geographic Endeavour. Even in this modern age it takes time and effort to travel this far off the beaten path – a pilgrimage to one of the last places on earth that is totally wild and pristine.

Straddling the equator, it’s hard to imagine a place on earth with a higher percentage of endemic species, including the famous Darwin’s finches, playful Galapagos sea lions, and the world’s only marine iguanas. What separates the Galapagos Islands from other places in the world is that 97% of the land is protected within the Galapagos Island National Park, and the islands are surrounded by one of the largest and most successful marine protected areas in the world. My hope is that it will always be this way.

The Galapagos is a dream for photographers. The animals show no fear towards humans, something that’s hard to comprehend until you experience it for yourself. Imagine being eye-to-eye with waved albatross and Nazca Boobies soaring along a cliff, sharing a moment with sally lightfoot crabs that don’t run away, encountering blue-footed boobies nesting along the trail, and Galapagos sea lions lounging on a white-sand beach.

Even though you can get very close to the animals, it still takes extra effort to make good images, compositions with clean backgrounds and good light. A cloudy day can help soften the harsh equatorial sun. Zooming in with longer lenses helps blur the background with a shallow depth-of-field. Getting down at eye level is another way to make effective portraits of the unique Galapagos endemic species.

A tripod it’s very useful in Galapagos, especially a light-weight carbon fiber model with quick-release plates that you won't mind carrying around. It’s key for shooting with slow shutter speeds, for example blurring the motion of the surf washing over sally lightfoot crabs or panning with a moving marine iguana.

It was a magical couple of weeks full of surprises and especially meaningful because of all the kids traveling with parents, grandparents, and aunts and uncles. These were not your average kids, mind you, but inquisitive little wisenheimers. Very lucky kids indeed.

Imagine being 8 years old and face-to-face with a blue-footed booby? Or swimming with sea lions, penguins, and marine iguanas? These are experiences that can transform lives.

“I didn’t want to go to sleep. Going to sleep would be admitting the trip is over,” exclaimed Campbell Brown, age 14, as he procrastinated on the last night of the voyage. Campbell came prepared, having a waterproof housing for his iPhone. While snorkeling off Champion Island, he found himself photographing sea lions underwater when he ran out of memory. “I couldn't believe it, I was bobbing in the ocean deleting iPhone apps so I could take more pictures, “ he said with a big almost embarrassed grin on his face. And he had some great images, one of which was used in the ship’s Daily Expedition Report posted online (Insert link to DER).

Another young man, Wilt, a 23-year-old photography student from Savannah Georgia, exclaimed, “I never thought you could get so tired chasing something that moves so slow,” after spending three hours observing Galapagos giant tortoises along their migration route in the highlands of Santa Cruise Island.

I’m also the lucky one, having the opportunity to explore and discover the wonder of Galapagos through eyes of children. Nature and photography brings them back to what's in front of them – timeless moments without video games, cell phones, and text messages. After showing little Ellie, a precocious 7-year-old, pictures of her as a giant tortoise walked by, she proclaimed, “Well, you’re not going to do any better than that,” walking off as if a Hollywood star leaving a movie set.

Scrolling Slideshow

Doors Off over Baja California

Aerial Photo Expedtion from Land's End to San Diego

Although we landed in San Diego a week ago, I still have not come down from the adventure of flying over Baja California during the first photo expedition of the

Baja Aerial Archive Project with LightHawk, WiLDCOAST, and iLCP.

This was not your normal flight-seeing operation, but an adventure full of uncertainty, military checkpoints, dirt airstrips, and, fortunately, an awful lot of good luck.

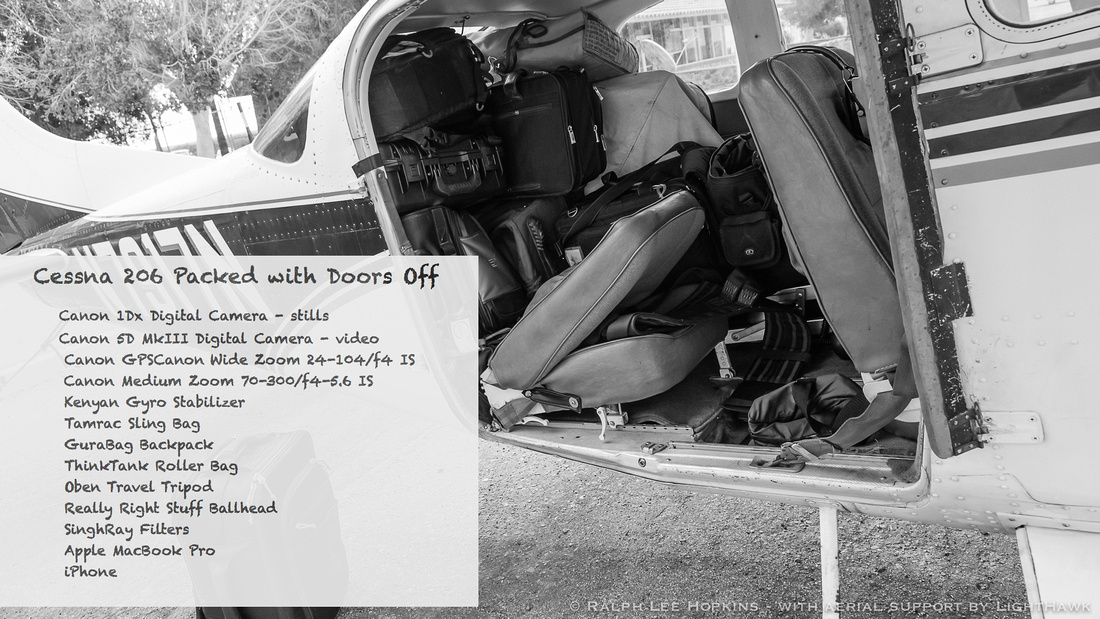

LightHawk’s battle-tested Cessna 206 is the perfect high-wing aircraft for aerial photography, especially flying with both cargo doors off. With nothing between me and the earth 1500’ below, I had the best seat in the house. For safety, I was strapped in a harness designed by the US CoastGuard, and also a seatbelt.

The most difficult part was avoiding sensory overload. Every take-off and landing was an adrenaline rush for sure, but once in the air at our exploring altitude, it was total bliss being in the moment with camera in hand as one incredible scene merged into another.

And we didn’t fly in straight lines either – covering over 3,500 nautical miles or 3.5 times the length of the Baja Peninsula in just 9 days.

Since tracking the location of the images was of critical concern, B&H Photo outfitted me with a Canon 1DX and GPS receiver, so that all of the 13,000+ images shot on the expedition are properly geo-tagged with lat/long co-ordinates. My workhorse lens was the Canon 24-105mm zoom, paired with the Canon 70-300mm zoom. Singhray ND grads and a polarizing filter helped narrow the exposure values between the bright landscapes and dark water. The camera was mounted on a Ken-Lab gyro-stabilizer to help minimize vibration, permitting me to work at shutter-speeds down to 1/500 sec. at ISO 800-1600 between f/4-f/8.

We had the best pilot for the mission Colonel Will Worthigton, a volunteer pilot and board member with LightHawk, and also a retired civil engineer with the US Army Corps. We also had the best operations manager, spotter and chief negotiator/diplomat, Armando Ubeda, Program Director for LighHawk. And teaming with me for video is filmmaker/photographer, Jeff Litton, a virtual energizer bunny always shooting while being squeezed into the tightest seat.

It was a photographer’s dream working with “the Colonel.” His plane-handling skills, together with his great appreciation for desert landscapes and understanding of coastal processes, helped us be in the right spot at the right time, flying not only for the best light, but also for the best composition. We worked well together, sometimes circling 2 or 3 times to get the best angle. At one point, we circled 700 feet above two humpback whales that breached repeatedly for 18 minutes.

Connecting the dots from our zig-zag itinerary, we flew from the over-developed tourist sector of Cabo San Lucas, to the noisy, motorized playground of San Felipe, then across to the Pacific Coast at San Quintin, skirting Picacho del Diablo, Baja’s highest point rising 10,000 feet above the sea in Sierra San Pedro Martir National Park. We flew almost the entire length of the mountainous coastline along the Sea of Cortez, the entire length of Magdalena Bay and the Sierra de la Giganta, circled over 500,000 nesting seabirds on Isla Rasa, and along the west side of Isla Ángel de la Guarda.

The Colonel was right when he remarked, after landing in San Diego, “If I hadn’t insisted we get back on course, we’d still be circling the blue whales off Punta Colonet.”

In between photo opportunities, there was plenty of time to ponder the amazing world we were flying over.

What impressed me the most was how much of Baja remains wild, with its vast expanses of desert wilderness, jagged mountain ranges, and endless coastlines. The Baja peninsula is where the desert meets the sea, a young landscape pulling away from mainland Mexico by the same plate tectonic forces that creates earthquakes in California, USA. In between the madness of Southern California and Cabo San Lucas remains one of the world’s last great treasures, not unlike the Galapagos Islands, with many endemic species unique to Baja and the islands along its shores.

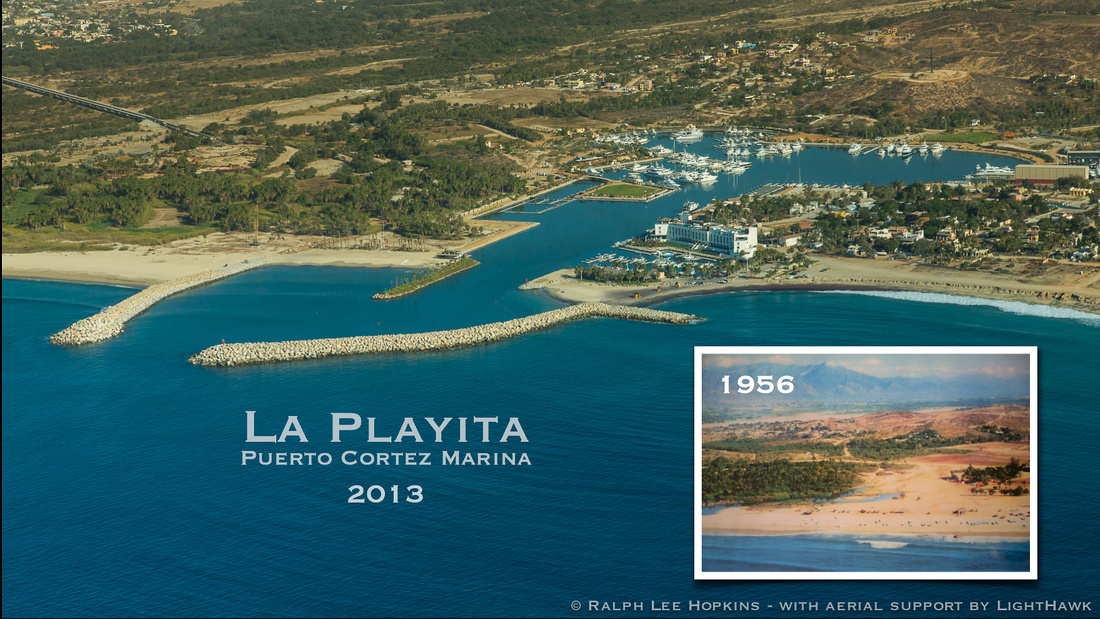

On the flip side, what also impressed me is the huge impact large-scale, mega-developments has on Baja’s coastline, with marinas being carved into wetlands, golf courses being watered in the desert, and high-rise hotels blocking the waterfront and limiting public access to the best beaches.

From the air I also learned how dynamic the coastline is with the barrier islands and beaches shifting with the seasons, and when breached, how coastal processes cause severe erosion, significantly altering the beach profile, while destroying nesting habitat for endangered sea turtles that come ashore to lay their eggs.

And I could also see from the air how fragile the coastal wetlands, estuaries, and lagoons are, not only the obvious impacts along the coastal zone, but also disturbances in the headwaters of the watershed, often hidden out of view from the ground.

But what I will remember most is what an honor it was to ask, “Colonel, Sir, any chance you can raise the wing just one more time? Thank you, Sir.”

Ralph Lee Hopkins

San Diego, California

Scrolling Slideshow

Exploring the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, Peru

In the flooded forests of the Amazon reflections are everywhere. Blackwater tributaries and oxbow lakes lead us deeper into the largest tropical rainforest on Earth. Floating quietly in the skiffs with outboard engines off, we listen to the sounds – the boisterous calls of macaws in the far distance, constant chatter of parrots and parakeets in the top of a nearby tree, the high-pitched squeaks of squirrel monkeys.

Reflecting back on my experience exploring the Marañon and Ucayali Rivers aboard the Delfin II, I will be forever changed by the experience. We've watched amazing birds from horned screamers with their crazy donkey-like calls, to the hoatzins with their punked-out head feathers. We've had great looks at monkeys of many varieties, including the secretive owl monkeys and the curious Monks Sakis, with their tropical fur coat. The Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve is the largest protected area in Peru, and in addition the great birding in a pristine wetland, it's one of the best places to see both pink and gray river dolphins. And we saw them on a daily basis.